水墨画の歴史

墨と水を含んだ筆を紙に着けると墨は思わぬ方向に一気に滲み広がってしまう。大多数の日本人が小学校の習字の時間に経験したことである。それまでの線描に加えて、その滲みを技術で制御して濃淡のグラデーションやフォルムで対象物のヴォリュームや明暗、さらに質感までも表わそうとしたのが水墨画で、8世紀ごろ中国の南部地域で生まれたという。やがて「破墨」や「溌墨」などの技法が生まれて、以来1300年余にわたって中国絵画の主流の一つとして受け継がれてきた。「墨に五彩あり」ともいわれてモノクロームの画面から色彩さえ感じ取ろうとする詩的な感性や精神性ともあいまって人びとに愛好された。

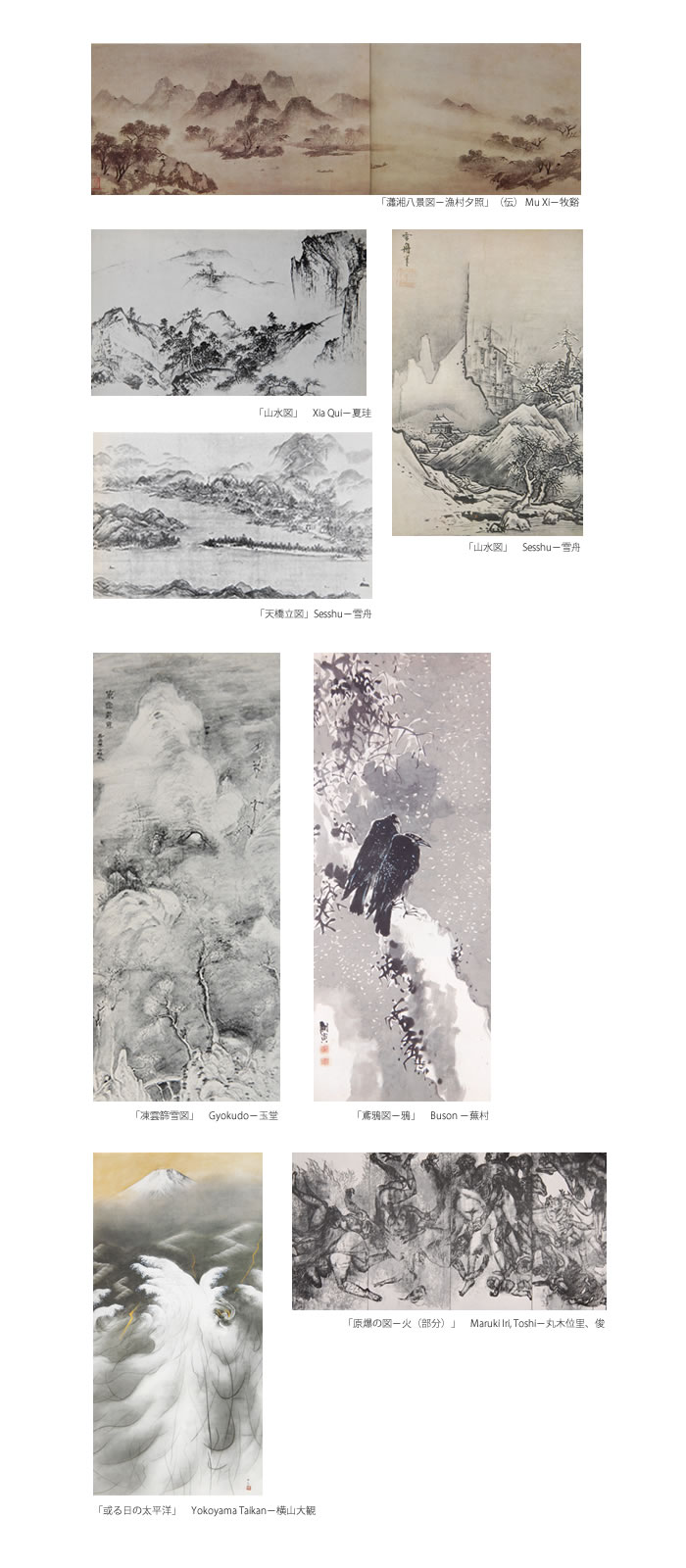

歴史に残る画家や名作を挙げればきりがないが、瀟湘八景図の牧谿や山水図の馬遠、夏珪、あるいは梁楷などが日本ではよく知られている。

水墨画は鎌倉時代(13世紀)、禅宗とともに日本に伝わった。禅宗の高僧の肖像画や禅機画(禅公案を題材にした絵画)が描かれた。周文、如拙といった名手が出たがいずれも画僧(画業を専門とする僧)であった。その後にやはり画僧の雪舟等揚(1420-1506)が現われて中国(明)に留学して院体画と呼ばれるオーソドックスな画法を学び日本に持ち帰った。「四季山水図」など謹直な筆使いの名作の一方で、晩年に描いた「天橋立図」ではどこか大和絵を思わせるような柔らかい風景図を描いた。これは水墨画の日本化ともいえるものだが、雪舟の水墨画は後世に大きな影響を与えた。水墨画は、また墨絵と

も言われ広く人々に好まれた。

室町の後期から桃山へ、金碧の障屏画とともに水墨の襖絵が書院や寺などに描かれた。

それらの多くを描いた狩野派を通じて山水や花鳥の水墨画が広まった。「松林図」で有名な長谷川等伯や雪舟の弟子で関東で活動した雪村周継らが日本的色合いの強いすぐれた水墨作品を残した。海北友松や久隅守景の名も忘れ難い。

江戸時代の前期、京都の俵屋宗達は大和絵風の画風を持つ装飾的な新しい墨絵を描き、

後の琳派につながる道を拓いた。江戸中期では池大雅、与謝蕪村、浦上玉堂らのいわゆる文人画が一期を画した。玉堂の、書の草書体にも似た柔らかな潤いのある山水画には

日本水墨画の一つの頂点を見る思いがある。また、蕪村が描いた雪中の鴉にはすでに近代の表情がうかがわれる。

京都、丸山応挙の四条派は自然観察を重視、西洋パースペクティブに近い視点から自然主義的な表現を追った。曽我䔥白、伊藤若冲、長澤蘆雪らの流派を超えた個性的表現も特筆される。また、西洋絵画にも大きな影響を与えた浮世絵にも風景など描写のそこここに水墨的表現がみられることは周知のとおりである。

明治期、脱亜入欧の思潮に沿って美術でも西洋志向が強まり水墨画も大きな衝撃を受ける。岡倉天心の影響を受けて、横山大観、下村観山、橋本雅邦あるいは小川芋銭らは西洋美術に対抗しうる新時代の水墨画を模索した。大観は朦朧体と称して輪郭線を排した墨の塗り重ねで立体感の表現を試みた。また、神官でもあった富岡鉄斎は独自な表現で足跡を残した。

第2次大戦後、丸木位里・俊子夫妻が水墨で大画面の連作「原爆の図」を発表し海外にも衝撃を与えた。 現在は日展、院展、創画会など日本画系団体で墨表現が見られるほか、「墨絵展」などグループ展、また、若い作家層にも墨により現代表現に挑戦しようとする動きが増えている。

中国には古来「気韻生動」という言葉があり、絵画を評価する際の最重要な点といわれる。その意味は難しいが、描かれたものから品格の高い生気が発揮されている状態、と私は解釈している。山水画の山容の元は長江流域の突兀とした石灰岩の岩山だといわれている。しかし、描かれた山はその写生ではない。滝や清流や樹木、逍遥する高士も含めて一種の理想郷の図示であり、自然の構成物を観念上で秩序に沿って配置した理念世界の展開であろう。一方、日本水墨の山水画では柔らかなカーブを持った山々や草木の様相をもとに大和絵的なあるいは短歌や俳句にも通じる日本的風土を内に籠めた情緒的世界の色合いが濃いと私には見える。山水画にかぎらず筆触から墨色まで日本と中国の水墨画には歴史的にかなりの違いがあるように思える。

History of Suibokuga (or Sumie)

If you apply on a paper a brush wetted with Sumi (China ink) and water, ink will spread into the paper and expand in unexpected directions - many Japanese have experienced this during calligraphy classes in primary school. Suibokuga (literally "water and ink painting") is the art of controlling this spreading of sumi and using density effects, in addition to the original line, to express form, light and even texture. It is said that this style appeared in southern China in the 8th century. Techniques such as haboku (broken ink, flung ink) or hatsuboku (splashed ink) were soon developed, and Suibokuga grew up as one of the main streams of Chinese painting. Since then, it has been transmitted from generation to generation for more than 1300 years. Driven by their poetic sensibility and spirituality, people felt attracted by the ability of Suibokuga to express "color" although the art piece is monochrome. This is probably why it is often said that "Sumi has five colors".

There are too many masters and masterpieces in history to name them all, but artists like Mu Xi (Xiao Xiang ba jing = the eight landscapes of Xiao Xiang), or sansuiga artists like Xia Qui, Liang Kai or Ma Yuan are well known in Japan. Sansuiga means "mountain and water landscape".

Suibokuga was introduced in Japan in the Kamakura period (13rd century), along with Zen buddhism. Artists painted portraits of high priests, as well as zenkiga (paintings representing koan, or subjects for zen meditation). Famous artists like Shūbun or Josetsu appeared, all of them being gasō (priests specialized in painting). Later on, Sesshū Tōyō (1420-1506), who was also a buddhist priest, went to China (Ming period), where he learned the orthodox technique of intaiga (court style painting). In opposition to the conscientious style of a masterpiece like Shikisansui-zu ("Landscapes of the four seasons"), in Amanohashidate-zu ("View of Amano-hashidate"), which he painted in his late years, Sesshū adopted a much softer style, reminiscent of yamato-e. Some people consider it as the Japanese version of Suibokuga, and it cannot be denied that Sesshū had a large influence on later artists. From that period, Suibokuga (also called "Sumie") became a very popular style, touching the heart of many Japanese people.

From the late Muromachi period to the Momoyama period, suiboku fusuma-e (ink paintings on sliding doors) were made as decorations for buddhist temples, Shoin pavilions, etc., along with kinpekiga (paintings using gold materials).

The Kanō School largely contributed to the development of these ink paintings representing landscapes (sansuiga) or flowers and birds (kachōga). Hasegawa Tōhaku, famous for his masterpiece Shōrin-zu ("Pine trees"), or Sesson Shūkei, a disciple of Sesshū who worked in the Kantō area, painted magnificent suiboku works with a strong Japanese sense of color. Artists like Kaihō Yūshō or Kuzumi Morikage should also not be forgotten.

In the first half of Edo period, Tawaraya Sōtatsu, of Kyoto, painted new decorative sumie works with strong yamato-e features, opening the way to the Rinpa School. In the middle of the Edo period, beautiful bunjinga (paintings by literary men) were made by intellectuals and writers like Ike-no-Taiga, Yosa Buson, Uragami Gyokudō, etc. It is not exaggerated to say that Gyokudō's sansuiga, with their soft and charming touch close to the sōshotai cursive style of calligraphy, are among the heights of Japanese ink painting. In Buson's Setchū no karasu ("Crows in the snow"), very modern expressions can also be pointed out.

The Kyoto-based Shijō School, founded by Maruyama Ōkyo, put emphasis on the observation of nature, and pursued a naturalist expression with an approach similar to the Western perspective. But artists like Soga Shōhaku, Itō Jakuchū, Nagasawa Rosetsu, etc. had personal styles which went far beyond this school and received much attention. It is also well known that in ukiyo-e, which had a large influence on Western painting, there are many elements close to suiboku ink painting, in the representation of landscapes, etc.

In the Meiji period, the inclination toward westernization appeared also in the field of art, along with the spirit of datsua-nyūō (rejection of Asia, adoption of Occident). Influenced by Okakura Tenshin, artists like Yokoyama Taikan, Shimomura Kanzan, Hashimoto Gahō or Ogawa Usen sought after a new style of Suibokuga that would be able to resist Western painting. Taikan tried to express plasticity through multiple application of ink and a brush work excluding outlines, a technique he called mōrōtai (vague forms). Tomioka Tessai, who was a Shintō priest, also left a very original style to posterity.

After World War II, Maruki Iri and his wife Toshiko presented a series of large-size ink paintings named Genbaku-no-zu ("images of atomic bombing"), which also attracted much attention abroad. Today, suiboku ink paintings are regularly presented in Japanese art organizations such as Nitten, Inten or Sōgakai, in group exhibitions like Sumie-ten, and the number of young artists challenging contemporary styles in Sumi art is increasing.

In China, there is the ancient expression "Qi yun sheng dong" ("kiin-seidō" in Japanese), which can be translated by something like "being animated with grace". It seems to be the most important point when appreciating an art work. This is a rather complex notion, but my understanding is that it corresponds to the condition when the painting exhales an elegant and refined spirit. It is said that the towering limestone mountains of the Yangtze River basin are the origin of the shape of mountains in sansuiga paintings. But the mountains which are actually sketched are different. It seems to be an ideal land, with waterfalls, rapids and trees, with men of noble character. It seems to be a conceptual world in which the elements of Nature are placed in order, according to a superior idea.

On the other hand, in Japanese sansuiga landscape paintings, I can see clearly a sentimental world filled with typically Japanese elements, like in yamato-e paintings, where mountains and trees develop beautiful soft curves, or even in haiku and tanka short poems, with their fresh and simple beauty. Not limiting to sansuiga, it seems that there are large differences between Japanese and Chinese suibokuga ink paintings, from the touch of the brush to the color of the ink.